By J. Levity

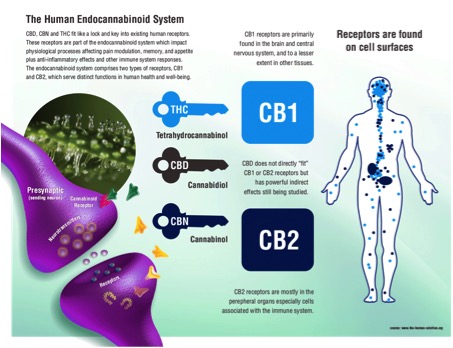

I inhale the vapour from the flowers of a female cannabis I have nurtured to maturity and carefully prepared. I instantly envisage being transported to a molecular landscape where her community of phytocannabinoids, including the notoriously passionate tetrahydracannabinol (THC) and her more passive sister cannabidiol (CBD), embark on their essential journey through my bloodstream. They are in search of suitable receptors to bind with and other, yet unknown, relationships to engage in. As these material processes embrace in their illustrious intera-actions, my own consciousness and the consciousness of the plant coalesce and arrive in a space that is neither human nor cannabis plant. A third space, perhaps.

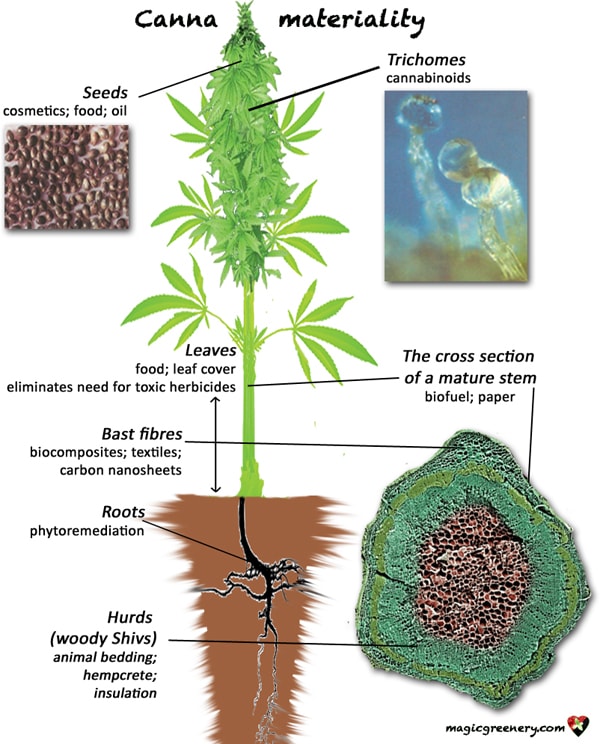

Meanwhile in a field in England, a group of eleven individuals are bringing in the harvest from a 5-acre, co-operatively owned small-holding. They are harvesting a crop of cannabis; a strain containing 5% THC and 15% CBD. This plants have been bred from a strain known for its fibrous qualities. Once the flowers have been harvested for the therapeutic cannabinoids, the hurds and fibres will go on to be used in building materials like hempcrete. Nothing is wasted. This is the vision or imagined dream of an Oxfordshire based cannabis co-op called Hempen.

The two visions, subjective experience and co-operative dreaming, demonstrate the entwined nature of the human-cannabis relationship (HCR). Cannabis is ubiquitous – a nature-culture ambassador spanning multi-dimensional landscapes from the molecular to the agroecological. On one hand, the interaction between chemical compounds found in the female cannabis flowers and an array of mammalian physiological and psychological processes. On the other hand, cannabis standing tall and defiant in co-operative, post-capitalist modes of production aimed at ameliorating current and future socio-ecological crises.

Multispecies landscapes

I first encountered cannabis at the end of the 1980s as a wide eyed 15-year old. In 1996, a short time after my first child was born, I cultivated and harvested my first female cannabis. Little did I know that I was to become her unwitting accomplice. Since then she has continued to offer me gifts. She has been a profoundly calming influence in my 28-year relationship with the beautiful mother of our three wonderful children. She has aided my parenting skills, bestowing patience and the gift of reflection upon me; and she is my most dependable collaborator in all my creative processes whether academic writing or music composition. I have suffered from a moderate to severe sinus condition for most of my life and I find cannabis to be an effective pain reliever for the headaches I suffer from. I also medicate with her when I have any digestive issues. She is an extremely efficient remedy for gut troubles.

It wasn’t until I attended Anna Tsing’s Firth Lecture at the 2015 Association of Social Anthropologists conference that I began to seriously consider the human-cannabis relationship as an academic enquiry. Tsing proclaims that “human nature is an interspecies relationship”. Listening to Tsing’s insights gifted me an epiphany. Humans and cannabis, from the molecular to the agroecological, are in a multispecies, symbiotic relationship. From Tsing I discovered Donna Haraway’s Companion Species Manifesto, which is focused upon her relationship with her dog Miss Cayenne. Haraway speaks of co-evolution and dissolving boundaries; I was enamored by how easy I found it to substitute the word `dog’ with the word `cannabis’.

Endocannabinoid system

Following the empirical research I conducted for my masters dissertation, I am now in little doubt that humans and cannabis co-evolved together. Both species benefitting from this unique mutual relationship. It is no coincidence that our mammalian bodies have evolved with a specific system that requires cannabinoids to operate successfully. This system is called the Endocannabinoid System (ECS) and when working efficiently it regulates a range of bodily functions. The ECS is a vast molecular landscape consisting of receptors in the brain and the central nervous system as well as in the gut lining and in other peripheral tissues. Biologist Robert Melamede describes the ECS as the master modulator. It is constantly multitasking, adjusting and readjusting the complex network of molecular thermostats that control our physiological tempo. Crucially, cannabis has evolved with trichomes that contain specific chemical compounds that bind with our mammalian receptors.

Why?

Some say that these sticky, potent smelling trichomes evolved to keep away mini-pests and mites. I think it is just as plausible that cannabis evolved with these qualities to enchant the human mind and enhance our physiology. Evolving the cannabinoid family for humans to commune with has worked out very well for cannabis. Humans identified the many qualities of being in relationship with cannabis a long time ago and would have sought out this plant for its fibrous and therapeutic qualities. This led humans to propagate cannabis across the globe. Cannabis is an evolutionary success story!

Unfortunately, nation states could not accommodate her wild and anarchist sensibilities and prohibited these relationships. Even our relationship with some strains of cannabis colloquially known as hemp, has been severely restricted. In the UK, the licensing process for growing hemp stipulates that the THC content of cannabis seeds cannot exceed 0.2%. Nation states constructed the hemp/cannabis binary and bred her to keep her THC levels down. In reality, the boundary between the two is less defined. For example, there is no botanical evidence to suggest that a rise in THC lowers the quality of the fibre and hemp-type strains are now being used for CBD medicine.

So, what do we call her? Hemp? Cannabis? Well, hemp is what we make out of the stems. More importantly we should be thinking about chemical taxonomies and what relationships are most mutually beneficial to human, plant and planet.

Taboo

Despite our essential relationship with cannabis it remains a taboo in all areas of culture, except within those cultures engaged in relationships with psychotropic plants. Even those involved in alternative cultures who proselytize discourses of social or environmental sustainability often refuse to acknowledge the vitality of this life-giving plant. This is classic head-in-the-sand at a time when policy reform, undesirably driven by free market ideology, is just around the corner.

While I researched my masters dissertation I was overwhelmed by the sheer amount of evidence as to the therapeutic qualities of cannabis. When I say evidence, I do not just mean the reams of academic journal articles screaming out about her therapeutic applications but also the countless anecdotal stories about how cannabis has stopped seizures in children, eased tremors in Parkinson’s and made significant contributions to the healing of some forms of cancer. The science regarding cannabis and cancer is still in its infancy but is already showing a lot of promise. Whilst I hear the concerns of those who have fears that high potency cannabis (wrongly referred to as skunk in the Daily Mail or the Telegraph) causes mental health issues, it is essential that we look at other factors before we lay blame on a plant or a human. Factors such as a person’s socio-economic position, potential heredity, and countless other emotional circumstances unique to an individual. Matters of the mind, soul and body must be approached holistically.

Agroecological Syndicalism

A final issue that I know is close to Sensory Solutions’ heart is the question of ethics in the means of production. Locking her away in a loft or a basement, in a tent under artificial lights may not be the most ethical of relationships. She has a spirit and is at risk of becoming our slave. Devout Rastafarians have a deep spiritual relationship with cannabis and, at the very least, require that she is grown in soil. I have grown wild, guerrilla-style outdoors; planting in spring and harvesting late summer/early autumn, and I have grown under an artificial light. When growing under a light I make time for her, sit with her, exchange energies. When I plant out, wild, she never fails to produce good quality bud as well as hardy stems perfect for hemp. Buds may not grow to be as full as they do under artificial lighting but I’m not in this relationship purely for that ends. Just seeing her out in the wild, flowering beautifully in the British climate is a joy to behold and I continue to make effective medicines from my clandestine outdoor activities. My aim is to one day be planting as part of an agroecological community co-op, growing outdoors, producing enough to last a small community through the winter months. This community would be a part of a much larger network of agroecological communities working co-operatively, providing support for one another. For the time being this vision remains a dream.

On an industrial scale, indoor grows using artificial lighting have significant environmental costs, requiring huge amounts of water and electricity. Furthermore, it prevents cannabis from existing in a wider plant community where she can contribute to soil health and ecological diversity. She is an ideal permaculture plant. Monocultures are reductive and always result in dysfunctional systems. However, we should be careful dismissing the loft/basement grower and their burgeoning relationships with cannabis. This kind of relationship may be the first intimate contact an individual has with a plant. There is a strong motivation built into cannabis cultivation to learn how to propagate a seed and nurture that seedling to maturity, all the time being mindful, keeping her healthy, happy and green. This kind of intense relationship could provide a vital doorway to a wider appreciation of horticulture and food growing. We know that being in a relationship with a plant is very good for mental health and wellbeing. Full Harvest Farm in Oakland, California, an urban permaculture project comprising of around six families demonstrate this. In a short film about their community, co-founders and couple, Karissa and Region Lewis discuss their own cannabis based local economy where they have also created a space for former inmates to come and learn about how to grow food and develop flourishing relationships. Cannabis plays a fundamental role in this incredible project.

So, the question is no longer whether the prohibition of the HCR should continue. That is a no-brainer. What we should be asking is what kind of relationships do we desire to engage in with this multifarious being we call Cannabis. It would be foolish to ignore the socio-ecological and ethical dimensions of this relationship. Patriarchy Inc. has begun to move the pieces with the intent of exploiting her gifts to maximise profits. Should we be silent? No.

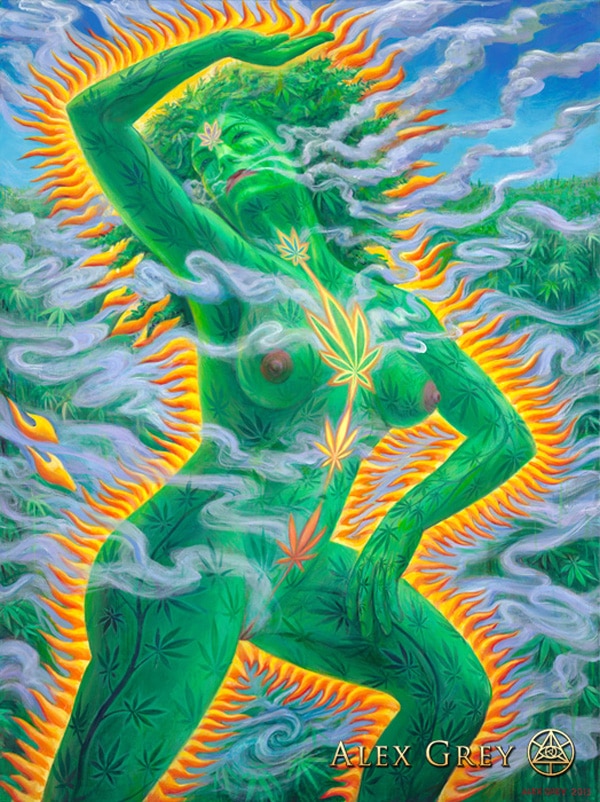

We must be shameless

in our veneration,

vigilant in the preservation

of the primeval,

ever evolving,

intra action with

the Green Goddess.

And together

we shall dance

into the unknown

future…