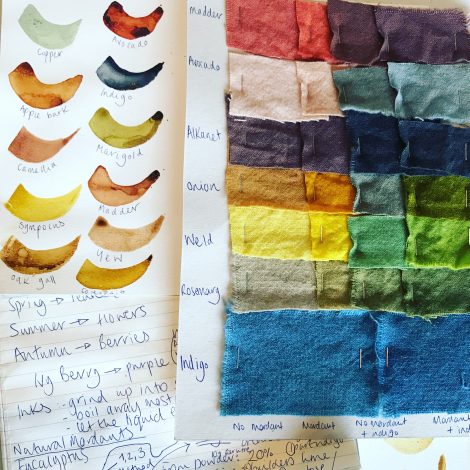

Flora is a natural dyer, grower and forager who loves to create inks, pigments, and dyes from plants for textile and paper. She demonstrates how we can create a diverse and vibrant spectrum of colours from natural plant dyes grown in the UK and food waste.

Flora is motivated by both a need to be environmentally sustainable and a desire to connect with nature. Over the past five years, she has embarked on a journey of connecting with the natural world through foraging and wild herbal medicine, in order to learn what means to belong to the land where she lives. Working with locally available natural materials to develop her own creative practice of drawing, printmaking and sculpting. She is currently studying herbal medicine with us Seed SistAs on the Sensory Herbalism Apprenticeship.

Flora runs workshops just outside Totnes in Devon, as well as offering online courses, exploring the alchemy of how we can create colours from the natural world.

www.plantsandcolour.co.uk

instagram @plants_and_colour

Here Flora tells us about the magical world of plant dyes

Nature connection through wild dyes.

My practice with natural dyes and inks is a process of learning how to live in a more close and practical relationship with the natural world. Working with seasons, wild plants and chemical free processes to create a culture around colour that is directly from and closely connected with the land where we live. Through roughly 13000 years of agriculture, we have become increasingly separated from nature. The synthetic dye industry, developed in the 1800s is one of the most polluting industries on the planet. Globally, the textile industry discharges 40,000 – 50,000 tons of dye into water systems every year. This cocktail of polluted water and chemicals, causes the death of aquatic life, contaminating soils and poisoning of drinking water.

It is also now clear that we are living in a time of human caused mass extinction and climate chaos. We need to find a new ways of living that are more connected with the natural world.

I am hugely influenced by a short time I spent in with the Ju’hoansi (The San Bushmen) in the Kalahari desert in 2018. These people hold a story of a rich way of life that is in harmony with the natural world, with old ancestral relationships with all animals, fungi, and plants who live around them such as the baobab, lions, the honeyguide bird, acacia trees, the springhare, lions etc. These relationships are built up through direct practical relationships, multiple generations of interactions and experiences passed on through stories.

When learning about the natural world, we love to to label things. But to learn the name of a plant can often be the end of our curiosity. When we learn not just the names, but we get to know a plant in it’s character through all seasons and stages of it’s life cycle, and we start to learn the practical uses. A deeper relationship develops and the name becomes almost irrelevant. We then start to integrate these useful plants and what we can make from them in to our lives. As we walk the land, we pass places where these plants grow and we harvest them every year, everywhere we go becomes imbibed with story. The stories of our own discoveries. Each one a small initiation in to the arms of the earth. Learning to live in relationship with the land. With this comes reverence and respect for the beings who live here.

Many wild dye plants are untapped abundance, If you don’t harvest them, no-one else will. Oak galls fallen beneath a tree the can be harvested to make a brown or black ink. There used to be a forgotten alleyway in Bristol planted with pink roses where I would harvest the petals all summer. Look out for over-grown camellia bushes, or fruit trees, the pruning of these are fantastic sources of dyes and inks. Look out for over grown stag horn sumac. This is an invasive tree that takes over gardens, all parts of this tree are useful for dyeing as they are high in tannins.

On the wild edges to the industrial estate where the buddleia flowers bloom (a yellow dye) in the summer become a place to harvest and appreciate the butterflies. We create these cycles for ourselves on the land. The places where we return to, layering up memories. The walnut trees in the car park (a brown dye), the abandoned eucalyptus plantation (pink and orange dyes), The weld patch by the sea. These are all places near where I live where I harvest every year. Pieces of my local map I have created in my mind. The land becomes re-named in detail based on my discoveries. No need to write it down, the experiences you have discovering the magic of discovery mean that you will never forget these places.

Through working with local wild plants, you develop a local colour palette. Responding to what is here. You can go out looking for something in particular but, unless you have already scouted out your foraging spots. you will get frustrated and come back empty handed most of the time. So it is important to be open to the unknown and respond to what you encounter. Being with, not doing to.

I am talking through the lens of working with wild dye plants, however, this approach is all about generalisation not specialisation. This practice is also applicable to wild food, medicine, and crafts, learning about birdsong, tracking, natural navigation, learning what wood is best for starting fires and what wood is best for cooking on. In the modern world, we are encouraged to be specialists. To choose one area of study and focus on and becoming an authority at that so that we can monetise our skill. When in the natural world, it is more rewarding to be a generalist because you are then able to give attention to all that you encounter rather than filtering out what can feel irrelevant. You are also more able to respond to what your encounter. We all have our own subconscious filters of what we notice.

When I go out, I am (slightly obsessively) attuned to noticing wild mushrooms. When I go out with others, I am amazed when they point out other things that I had not noticed such as bird calls, animal tracks or signs. There so much information around us, as we tune in, we start to be able to read the stories of the land, to notice the plucking post of a goshawk, what they had for dinner, and when. We can start to know where specific species of mushrooms are likely to pop up each year. We start to know where to look on unknown pieces of land for particular plants based on the topography. We start to create our new migratory foraging routes, following the flow of abundance throughout the year. For me, the starts with the first warm sunny day imbolc with the harvesting of tree sap, and ending with icy velvet shanks in the midst of winter.

Before synthetic dyes were invented in the 1800s, all dyes and pigments had natural sources. They were extracted from plants, rocks, earth minerals, or insects. Cultural identifies were defined by the colours that could be created from locally available materials. This gave colours symbolism and meaning connected to how the colour was made and who used it.

Everyone would have worn the colours of the land. We would have had enduring relationships with these garments due to the energy and resources requited to create the fibres and the colours. Fabrics would have been cared for, repaired, and reused.

Sharing the practice of creating colour from plants is about empowerment and self care through developing/deepening our relationship with nature. As we learn how to sustain ourselves with wild natural materials, we become part of the natural world again.