Us Seed SistAs love plants, as you well know we are completely passionately potty about nature connection – we met Dr. Sam Gandy at The Medicinal Mushroom Conference and also at Breaking Conventions International Psychedelic Conference and here he shares some of his journey and research into the wonders of nature connectivity utilising Magic Mushrooms….. …….

One of the most negative and dangerous consequences that has followed in the wake of the success of our materialistic, technological civilisation has been a growing human disconnection and alienation from nature. This has very serious implications for both our mental health as individuals, as well as the health of the wider biosphere.

Nature connectedness or relatedness is a measure of one’s self-identification with nature, an individuals’ experiential sense of oneness with the natural world. It is something direct and emotional. Nature connection can be considered similar to the concept of biophilia, defined as “the connections that human beings subconsciously seek with the rest of life.”

There is a significant body of research to show that high ratings of nature connectedness are strongly associated with reduced levels of anxiety, greater life meaning, vitality and happiness, and improved psychological well-being. High ratings of nature connection are associated with higher valuations of intrinsic (e.g., personal growth, intimacy, community) as opposed to extrinsic (e.g., money, image, fame) aspirations.

Nature connection is also considered one of the strongest predictors of pro-environmental behaviour. It seems that an emotional, empathic connection to nature is needed to motivate behavioural change, and that concern arises as a side effect of this deepening connection. Pro-environmental awareness is also deeply tied to prosociality, or the intent to benefit others, with one increasing the other. This is suggestive of a positive expansion and externalising of one’s awareness and concern that follows in the wake of a growing connection to nature. The early heyday of Western psychedelic culture coincided with the rapid growth and expansion of the environmental movement, which has led some to argue that psychedelics may have contributed to the impetus of modern ecology movements.

Nature connectedness is distinct from nature immersion, bringing independent and additive benefits, with these having a positively reinforcing, synergistic relationship. People with a strong connection to nature are more likely to spend time in nature, and so experience the wider benefits of nature immersion, and more contact with nature tends to result in a greater connection to it. Nature connection also enhances some of the benefits of nature immersion, including well-being, mood, attention, ability to reflect on a life problem and the perceived restorativeness of natural settings.

Much of the modern research linking psychedelics to enhanced nature connectedness has involved psilocybin. Psilocybin certainly isn’t necessary to enhance nature connectedness, but it can yield a radical and enduring shift in perspective in some people who tend to place more value in their relationship with nature post-experience. Such a shift may be valuable for those who have grown up without much contact with nature, as childhood contact with it is a strong determinant of nature connectedness and contact in later life. The evidence that psilocybin can facilitate a sustained shift in the way people relate to nature is important, as there is a lack of interventions that can increase nature connectedness in an enduring way. Much like personality traits, environmental attitudes can be resistant to change. But research on psilocybin has shown it to have the power to catalyse shifts in both.

Psychedelics can also increase cognitive flexibility, self-transcendence, facilitate positive changes in aesthetic experiencing, and catalyse experiences of awe, all of which have been linked to nature connectedness.

Feelings of interconnectedness with nature, of being part of nature, seem to be a primary facet of the psychedelic experience, described over and over again in experience reports, research surveys, and key historical accounts of early psychedelic experiences. There have been a number of studies showing that psychedelic users rate more highly on measures of nature connectedness, including one that found that lifetime usage of classical psychedelics (but not other substances examined) resulted in increases in pro-environmental behaviour through an increase in people’s self-identification with nature. However these past studies have been unable to demonstrate a clear causative effect of psychedelic usage changing people’s nature connectedness.

A study conducted at Imperial College a few years ago looked at a number of participants in a psilocybin-major depression study. While the study was small, there was a robust and enduring shift in people’s nature relatedness observed up to a year post-experience. Interestingly, such shifts can occur even in the context of a clinical setting lacking in nature. This hints that this may be an intrinsic property of the psychedelic experience to some degree.

Recent research has shown that experience with psilocybin can yield enduring increases in mindfulness, even outside the context of a meditation practice. This is important, as there appears to be a positive, synergistic relationship between mindfulness and nature connection, and mindfulness appears to mediate the relationship between nature connectedness and well-being, while boosting mood when spending time in nature. Psilocybin can also increase personality trait openness to experience, which among other things is associated with nature connection and pro-environmental awareness and the propensity to experience awe.

A recently published study found that usage of classical psychedelics (including psilocybin mushrooms, LSD, ayahuasca, DMT and mescaline cacti) enhanced nature connectedness in a large, healthy population.

Of the various findings, a very clear effect of the amount of past lifetime psychedelic usage on people’s baseline nature relatedness was observed. There was also a clear effect of psychedelic use increasing people’s nature relatedness post-psychedelic in people who lacked any previous psychedelic experience, and these increases were enduring, being observed 2 weeks, 4 weeks and 2 years post-experience. There was a concomitant increase in nature relatedness and well-being (echoing other research), and the increase in nature relatedness was found to be mediated by the perceived influence of natural settings and experiences of ego-dissolution under the psychedelic.

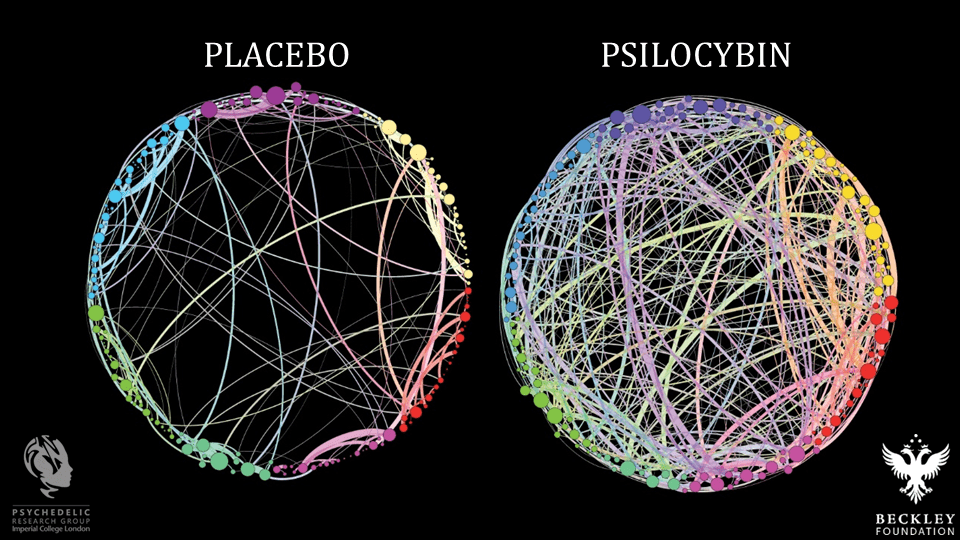

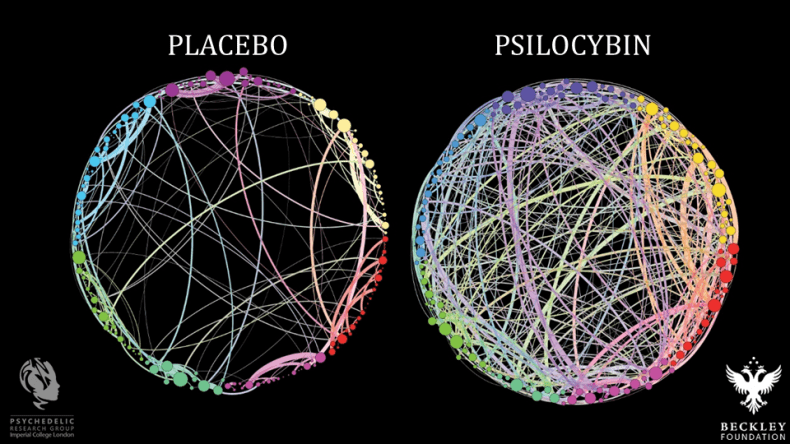

Previous research has also highlighted a link between experiences of ego-dissolution and enhanced nature connectedness. Ego-dissolution occurs when a brain network known as the default mode network (thought to be a fundamental component of the neural basis of the ego or our subjective sense of self-identity) is relaxed and deactivated under the psychedelic. This appears to result in perceived boundaries between self and other dissolving, resulting in an expanded perspective of self-nature overlap. The memory of this perspective shift seems to be enduring.

An account from one of the recent Imperial College psilocybin studies and another from Reddit highlight how this feeling of deepened nature connection may come about:

Before I enjoyed nature, now I feel part of it. Before I was looking at it as a thing, like a TV or a painting. [But] you’re part of it, there’s no separation or distinction, you are it.

“Most beautiful experience of my life. Trees, grass, flowers, clouds. It was like I’d never seen any of them before, they’re so colorful and intricate. I’ve been staring at TVs and phones for so long, mushrooms really brought back the appreciation for the world around.”

As research with psilocybin continues to gather momentum, it is likely to be medically integrated for clinical use in the coming years. It would perhaps be a shame if its use was limited to a clinical setting, as its potential extends beyond this. Given that psilocybin can increase our connection to nature, and the implications this has for our mental health and well-being, coupled with the inherent and intrinsic therapeutic properties of natural settings, psilocybin could hold great potential as an agent of ecotherapy. An important component of the experience of both psychedelics and nature is the experience of awe, with awe being associated with increased well-being, life satisfaction, prosociality and reduced inflammation. Awe may be more prominent in natural settings. Plans are in the pipeline for a more rigorous study to explore the capacity of psilocybin to enhance nature connectedness.

Experiences of awe, wonder, unity and interconnection are also fundamental components of the overview effect, described by astronauts when viewing the Earth from space. It seems that psilocybin may provide an alternative and more accessible route to a similar transformative perspective.

A growing alienation and disconnection from nature can be considered to be the root of the global environmental crises we face, driving the sixth mass extinction event we have entered into due to the actions of our species upon the biosphere. Given how important both nature connectedness and contact are for human mental health and well-being, our growing disconnection from it is also likely fuelling the growing mental health crisis.

Reconnecting humans with nature and identifying any means through which we can reverse our disconnection should be considered a common goal and urgent priority shared by all, with there being a notable lack of interventions for reducing people’s environmentally destructive behaviour. As a group of ecopsychologists concluded at a conference almost 30 years ago: “if the self is expanded to include the natural world, behaviour leading to destruction of the world will be experienced as self-destruction.”

Given the demonstrated capacity of psilocybin and other psychedelics to facilitate this increased human-nature connection, it would seem their widespread prohibition is not in the best interests of our species, or the biosphere at large. What if rather than vilifying these compounds, we held them in the same high regard as some indigenous groups do? How different might our global future look if that were the case?

One of the grandfathers of the modern psychedelic movement, the great chemist and inventor and discoverer of LSD, Albert Hofmann, came to view the capacity of psychedelics to connect us to nature as perhaps their most important fundamental property. He took great joy in hearing of nature deprived urbanites having their eyes opened to the wonders and beauty of nature through their LSD experiences. In his book ‘LSD: My Problem Child’ he said:

Psychedelics are not a panacea. They are not a magic bullet, and they are not going to do the hard work we need to do to restore and regenerate the increasingly degraded biosphere. However, if used with care and in the right context, they could play a role as catalysts of connection, by addressing the psychological disconnect that lies at the root of what the social scientist Renee Lertzman recently referred to as our ‘environmental melancholia’. We urgently need to transcend our sense of separation and regain our connection to nature. I can’t think of anything more important at this time.

Sam has a PhD in ecological science from the University of Aberdeen and an MRes in entomology from Imperial College London. He is a writer, speaker, amateur mycologist and has a lifelong love of nature and wildlife. He has been fortunate enough to conduct field research in various parts of the world including the UK, Kefalonia, Almeria, Texas, the Peruvian Amazon, Vietnam and Ethiopia. He also has experience of working in the psychedelic field, as a past scientific assistant to the director of the Beckley Foundation, and currently as a collaborator with the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London. His research is focussed on the capacity of psychedelics to (re)connect our increasingly disconnected species to nature, for the potential betterment of humanity and the biosphere at large.